There is one surefire thing any aspiring young player shares with Leonel Messi, Cristiano Ronaldo, and Wayne Rooney. They dream – or dreamed – of leaving behind the dusty or muddy makeshift football pitches of their hometown for the bright lights of the Nou Camp, Bernabeu, or Old Trafford.

But talent alone won’t drive you down the road to those theatres of dreams. You need the hunger but you need to be noticed; you need luck; you need connections; and you need good judgment to make important decisions.

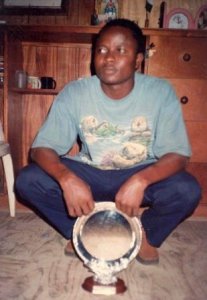

This is where we meet Matthew Edafe, who thought he had every box ticked. Like pretty much every other teenager, playing professional soccer seemed a fantastic way to make money. It was not a job. Like many teenagers, it was also a way to break his family out of a desperate cycle of poverty – even if it meant leaving his home, his town, his country, for faraway Europe.

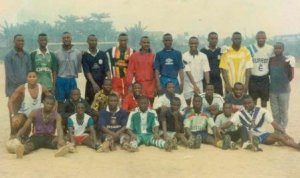

Edafe was from a small city in Nigeria, a country that has produced generations of soccer stars now known around the world: Jay Jay Okocha, Sunday Oliseh, Samson Siasia, Celestine Babayaro, Nwankwo Kanu, John Obi Mikel.

For sure, Matthew had raw soccer talent but, like many parents around the world, his mother preferred he use the money the family had saved for university to study to be a doctor or lawyer or accountant. But when a guy claiming to be a player agent turned up in town, driving a big car, saying he knew a lot of important people, and saying had taken other young players to Europe, well, it was difficult to ignore what he said.

“He showed some photos he had taken with white people,” explains Edafe, today. “I don’t know how they do that – maybe it’s Photoshop – to show that they had the opportunity to travel.

“They bring a document that says they want to take 30 young players abroad; that for the very first game you play, any game, a trial match or whatever, they will give you $2000. When you sign the contract you will start earning anywhere from $10,000 to $20,000.

“The only thing that comes into your head during all that is the exchange rate from dollars to [Nigerian] naira. It is a question of your dream versus your reality. The person who is speaking looks well fed. You don’t even ask a question.

“The African is brought up to respect and not question their elders. The elders are not supposed to lie. The elders are supposed to be a paradigm of knowledge and honesty and wisdom. So the question is, how do I get myself onto this list of 30 players? Then the agent comes up with a ‘contribution’ you have to make, ranging from $2200 to USD$5000.

“People who are desperate then get more desperate, and sell their property, family land, houses, parents’ cars, to get on this team. But the agent says that we’re scheduled to play about 30 games so you will get the money back and more.”

If you were poor and desperate and had a dream, what would you do? Possibly what Matthew Edafe did do. He was told that once he paid the required fee, he would travel to Spain with the “team” of other young Nigerian hopefuls. Matches and a trial with a team in Spain’s second division would await. This was the big chance. There was no choice to make.

“My mother borrowed a lot of money,” Edafe explains. “She tried to make sure I made something out of life. We were really from the slum. Really poor people.”

But this journey would be no luxury trip, the way many professional footballers travel in the first class section of a jet or on comfortable air-conditioned VIP buses. With 22 other players, Edafe left Nigeria for Senegal before heading for Cape Verde – by boat. There, on the island, they were promised a training camp to prepare for Spain.

According to Edafe, after four days on Cape Verde, some white men, speaking a language none of the players understood, came by to watch the Nigerians train. They left without speaking to the boys. So, too, did the agent. Just like that.

The “team” was soon tossed from its hotel (prostitutes were among the other guests, Edafe recalls) and the players worked out what might have seemed obvious to others. There was no deal, no game, no tour, no plan, no money, and most of all, no agent.

Edafe was stuck in Cape Verde for 11 months. He says he lived on the street and did all kinds of jobs before he met a local girl who introduced him to her father. That earned him a job in a boatyard and led to a trip back to Nigeria on a ship.

“I was 20 years old in a strange land,” says Edafe. “We heard on the street that this is what normally happens. I thought I would never see my family again. I didn’t know what to do. I lost a chance to further my education and I lost a chance to play football. I was in a daze. There was no going forward. There was no going back.”

In Paris, Jean-Claude Mbvoumin, a former professional player who had a modest career in France and also represented Cameroon, receives calls every day from players just like Matthew Edafe. For the past 10 years, Mbvoumin has run Foot Solidaire, an NGO that assists young African players dumped in Europe by fake agents.

There are no accurate statistics for the number of players from Third World countries scammed and marooned in Europe - the trade is illegal, players are not registered, and are often embarrassed about their plight – but Mbvoumin counts over 1200 individuals he has personally assisted.

He says most arrive in Europe via the broken promises of agents or private coaching academies that claim associations with European clubs. According to Mbvoumin, professional clubs in Europe are aware of the crime and corruption in player recruitment that is now systemic.

As well as Nigeria, you can add Ghana, Cameroon, Mali, and Cote D’Ivoire as major sources of young players. In a route different to Edafe, clubs in Africa will recruit players and promise to on-sell them to a club in yet another country which may have a reputation as a launch pad for a fabled career in Europe. The dreams sold and routes taken are similar to that of human trafficking more commonly associated with prostitution and illegal immigration.

“We know that this trafficking is guided by European agents, illegal agents, and the recruiters from professional clubs,” says Mbvoumin.

“Today you have many roads. Ten to five years ago, we had the fake agent recruiting in Africa and taking money from a family. The children pay for the ticket and they get to Europe. Sometimes they make it to a professional club for trials but sometimes the agent abandons the young boy on the street.

“Today there is another way – inside Africa. We know that in Ghana there are many partnerships with European clubs and they are recruiting from all over West Africa. In Togo, in Cote D’Ivoire, in Benin, in Nigeria. Children are also going from sub-Saharan countries to Morocco, Tunisia, and Egypt.

“These countries are the first step – the final step is to be in Western Europe [but] in countries like Serbia, Croatia, Romania or Poland it is much easier to get a work permit. Once they get that permit they can go to another country. There are also other roads that take you to America, Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia. It is now an international market but the main goal is to come to Western European football.”

When not occupied by its own corruption allegations and Executive Committee shenanigans, FIFA has several regulations in place aimed at restricting the trade of young players. These include banning players under the age of 18 moving internationally unless the entire family moves too.

Also, FIFA requires all member associations to register all players attached to training academies affiliated to local associations. But the world governing body also acknowledges that it has no jurisdiction over private academies.

“Soccer players are in the grip of commerce of which they are the pawns,” says Roger Blanpain, a lawyer and former head of FIFPro, the international players union.

“They are bought and sold like cattle. This amounts to human trafficking. At all levels. Contracts are concluded at young ages, like 16 years old for five years and so it starts. There is an ongoing trafficking in youngsters from Africa and South America, who are dumped if they do not succeed on the soccer market.”

According to Blanpain, the steady rise in the transfer price and salary of players means many European clubs are increasingly turning to non-European markets to fill out their player rosters. In a basic globalization lesson, African and South American players are cheaper than those from Europe.

Throw in the commissions earned by player agents - in Europe alone agent earnings can amount to over USD$285 million a year – and you have a recipe for exploitation. According to FIFA, only 25% of transfers occur through regular, licensed, agents. But agents are difficult to stop and exploited players usually claim they do not know the full identities of those who dumped them.

Jean Claude Mbvoumin says that while FIFA’s regulations are a step in the right direction, until there are alternatives for young players dreaming to be the next Drogba, Essien, or Eto’o, exploitation will always occur.

Mbvoumin, whose organisation is funded by private donations, has met with FIFA boss Sepp Blatter but diplomatically says there is a communication problem with the governing body.

“Mr Blatter is a football authority and he gave Foot Solidaire his support in 2008. But behind that, we don’t have very good communication. I wrote a letter to him. It was not to say he was bad but just to say today we have an emergency in Africa.

“Football is not just a sport today. In Africa you have many economic and social problems. Football is a way to try and improve lives but FIFA has to make many projects in Africa. We need the best of the best going to Europe and the rest must play in a local championship. But there are no real championships in Africa. So the children want to go to Europe. We must develop football in Africa.”

In Lagos, Matthew Edafe is now trying to educate young players so that others don’t share his experience. His mother died in 2010 at the age of 52. Edafe believes his experience contributed to her decline.

“Education is not the final solution but it is part of it,” he says. “A player like Ronaldinho is informed and involved about what happens to him at an early age.

“Here, in Nigeria, you have to understand that in this country it is dog eat dog, survival of the fittest, and everything has a price.

“This trade is evil. Any trade that makes you exploit people and destroy their future is evil. It is another version of slave trade.”

Great article one that needs to be in the New York Times.

[…] of a surprise that the rest of the world can now read about match-fixing, illegal transfers, human trafficking, money laundering, Swiss bank accounts, bribery, racketeering, falsification of contracts, etc. as […]